Big Shot, Part 2: My Father

By Simeon Den

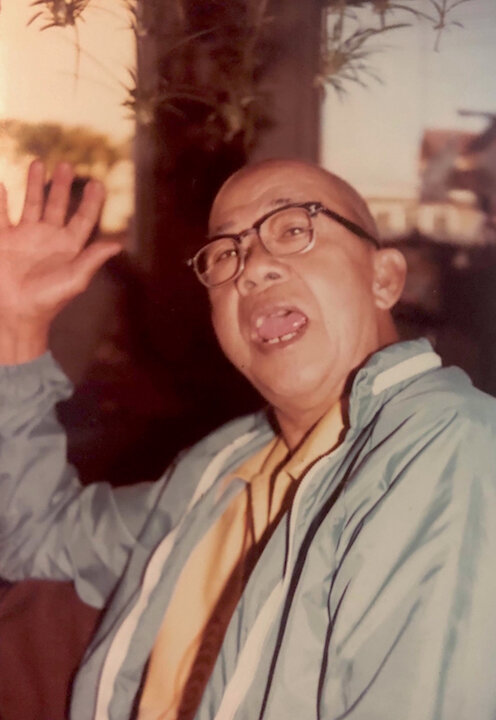

Simeon’s father, Deogracio Secretario

My father was 14 years old in 1921 when he left his family and emigrated to Honolulu from San Manuel, Pangasinan, a province of Ilocos Norte in the Philippines. He was recruited and hired as a sugarcane field laborer, did not speak English at the time, never learned to read or write (save for his signature). Although he did not have a birth certificate we always celebrated his birthday on March 26, “somewhere around there,” he guessed. When he was 36 years old, in 1943, he married my mother, who was 15 at the time, and they divorced seven years and five children later. My sister and I were the youngest and were left to be raised by my mother. When I was ten years old, our branch of the family was living in Las Vegas and, for various reasons that I can’t remember, my sister and I chose to return to Hawaii to live with my father and our other three siblings. It had absolutely nothing to do with my mother being unfit to raise us or Child Protective Custody or whatever. I’m thinking, it was because we were homesick for Hawaii. But, for sure, it was not because he had lots of money and could afford to give us more stuff… On the contrary!

My father was a dishwasher at the world famous Royal Hawaiian Hotel. I loved going to pick him up everyday after school, riding in the back seat of our green Desoto sedan with my older brother driving through the gate reserved for the employees only. In slavery-speak, working at that glorious Pink Palace could have been more likened to working in “the big house,” but not to me. To me, it was like going to a beautiful different, NICE looking place. The people on the other side of the fence looked “nice,” dressed “nice,” and all smiled nicely. I was proud of my Dad for working there and my siblings used to tease me because my father absolutely doted on me, or, perhaps, they just knew better.

Simeon Den (far left), his father (center), and family

When I got older, our father-son relationship became typically strained and our language barrier only exacerbated the situation. I loved and respected my father but because of our inability to effectively communicate, his relationship to me became more like a grandfather from the old country than a father like my friends had fathers. Despite that, my way of honouring him and expressing love was to excel in everything I undertook and to make him proud of me. So I did. Straight A’s, student government officer, Most Likely To Succeed, anything to gain his approval.

Despite his humble station in the American Dream world, my dad was very well liked and highly regarded in our own world, the Filipino immigrant community-world. I used to think that his popularity was due to his reputation of being a “good guy” but he was much more highly regarded than that. My father was one of the two official bird handlers at the weekly cockfights that were held every Sunday afternoon. In our post-PETA world today, cockfights are barbaric, grotesque events and gargantuanly worse than politically incorrect. But in pre-Statehood Hawaii, cockfights were weekly celebratory events. They were, for sure, gambling events and my father was an integral part of that sport, and cock fights were much, much more than an occasion for merely gambling.

I looked forward to these “chicken fights” which were like big, weekly block-parties or mini cultural festivals held every Sunday in the middle of the cane fields to avoid the eyes and reach of the American law. The old women came to sell fresh home grown Filipino vegetables and ono (delicious) mouth-watering desserts (mostly crisply fried dough sprinkled with powdered sugar), and it was a social gathering more for the whole community to share the news and gossip of the day rather than the main activity of the cockfights. Here, my father was an Elder.

In the haole world, my dad was not an Elder. Rather, he was a short Filipino man who could not read or write. As a 9 year-old, I do not remember making or having a judgement of that fact, but I have a now painful memory of him asking me to teach him to read. I remember sitting with him one afternoon in our backyard squat-sitting on a low wooden bench surrounded by the ripe smelling fighting-chicken coups, under the clothesline where freshly washed and starched laundry was hung out to dry, the warm tropical sun illuminating us as I attempted to teach him to read. I didn’t question it at the time but, in retrospect, I realize that my father was terrified to admit to anyone that he could not read. A closet illiterate, too proud and frightened to admit his shame, he sat with me on that frustrating afternoon struggling to read from the children’s primer, “Fun With Dick and Jane”. We did it just that once. It breaks my heart now as I recall it. It breaks my heart that I may have seemed impatient. It breaks my heart that we didn’t succeed. It breaks my heart.

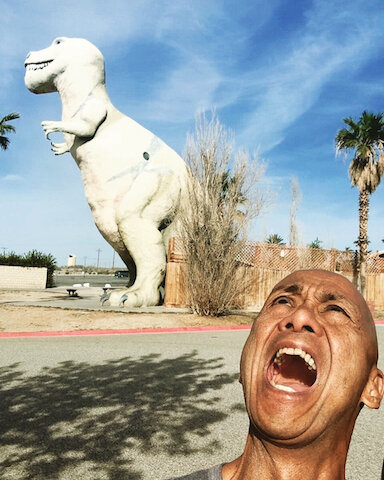

Simeon Den

Later on, I remember he tried taking an adult education course at the local high school but apparently it didn’t suit him. He never did learn to read and I never knew if it was because he was too embarrassed, didn’t care to put in the effort because we could do the interpreting for him, or if he was just plain stubborn.

Quite probably because of his lack of education the plan to Americanise me included a good education. I was a quick learner and self-motivated, so I excelled. But the more I excelled the greater became my disconnect with my father.

To be continued.

***

Listen to Episode 2 “Big Shot” on Simeon Den’s Podcast here.

***

Simeon Den (born Deogracio Dingo Secretario) is a 2nd generation-Filipino, born and raised in Honolulu, Hawaii; Los Angeles-based dancer/choreographer, author, director, photographer, Arts educator, and Performance Art practitioner with a 50-year professional performance career in concert dance, theater works on Broadway, National tours, and television. His current art practice is fine art photography and Butoh Dance, the avant garde Japanese Performance Art discipline. He has worked with luminaries including Jerome Robbins, Hal Prince, Shirley MacLaine, Stephen Sondheim, Lena Horne, and Yul Brynner and affiliations with the Alvin Ailey and Martha Graham dance companies,

Den attended the School of Visual Arts (NYC/Photography), University of Hawaii (Asian Art History), University of Massachusetts, and is a magna cum laude graduate of UCLA School of World Arts & Cultures (Dance & Performance Studies). He has taught internationally including CalArts, American Musical & Dramatics Academy, and the London School of Contemporary Dance.

Den is the Managing Director of the Agnes Pelton Society, a 501c3 non-profit arts and Arts education advocacy and the co-owner of the historic Agnes Pelton House in Cathedral City, California, whose mission is to support the legacy of the posthumously celebrated historic painter, Agnes Lawrence Pelton. His creative team is developing “The Agnes Pelton Song Cycle,” an evening-length, contemporary classical music, concert piece of original vocal music, dance, and Spoken-Word inspired by the “Agnes Pelton, Desert Transcendentalist” retrospective of Pelton’s abstract paintings; currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art and culminates at the Palm Springs Museum in Summer/2020.

Most recently, having never done drag performance before, Den entered the Cathedral City Drag Race pageant as "Sue Madre.” Although Sue competed the requisite drag queen lip-sync for talent, her secret weapon was to sing live and Sue Madre finished in Third Place. As his drag persona, Sue Madre, he moderates the podcast, "Old Gay/New Gay," archived on KGay Radio in Palm Springs.